The following is an essay, in letter form, written to the teacher of my high school Utopia/Dystopia Fiction class. I dove into the material of the course, seeing so much of myself in these narratives of destruction and isolation. Reading it now, I understand the sense of connection I felt towards the apocalypse. It was senior year and I was about to leave Minnesota, about to transform, forever, my life there into a memory. The final assessment of the semester was this letter, written in personal voice. The only requirements were that we discussed five works and, at some point, correctly used a semicolon. Enjoy my reflections on a pivotal semester in my life and my now cringeworthy 17-year-old prose.

Works included: Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963).

//

Hello,

What a week it’s been. I’m writing you from the corner of a crowded Caribou Coffee as the sun dips below the Chipotle across the street. Oddly enough, it’s kind of pretty. Sipping from my third iced coffee of the day, I’m struggling to stitch together the thoughts I have wandering around. I’m beginning to realize my essay writing process relies on the failure of one or two ideas before settling on a topic. Yet this time, I’m without preparation. I simply want to charge into this letter, writing from the heart, in the best way I know how. However, as I continue to think about this essay, I’m realizing the genius of the assignment. I seriously see no better way to wrap up this course than with self-reflection and the inspection of our world through the observation of others. Throughout the course I’ve been on a personal journey. All of these lessons have bounced out of the text and into my life, leaving me to incorporate these texts, no matter what world they’re from, into my own. This letter very well might be a love letter, one to this course, to literature, to discussion, to allegories, to the english department, to utopia. No matter the subject, I look back on my experiences this semester with nothing but joy and admiration, and I’m choosing to focus on that rather than any stress I may have developed trying to sort out the events of the Birthmobile crash or the Syphilis outbreak that tragically killed Ofglen (class lore created en masse by imagining tragic events in The Handmaid’s Tale). I digress.

August/September — Station Eleven

“I repent nothing,” read page 107 of Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, triggering an identity crisis that would last me well into the evening. I ultimately ended up re-reading that same page over ten times, laying on my floor as the digital clock on my laptop struck two. Miranda Carroll reminded me of myself in a way that surprised me, and scared me all the same.

“In four months Miranda will be back in Toronto, divorced at twenty-seven, working on a commerce degree, spending her alimony on expensive clothing and consultations with stylists because she’s come to understand that clothes are armor; she will call Leon Prevant to ask about employment and a week later she’ll be back at Neptune Logistics, in a more interesting job now, working under Leon in client relations, rising rapidly through the company until she comes to a point after four or five years when she travels almost constantly between a dozen countries and lives mostly out of a carry on suitcase, a time when she lives a life that feels like freedom and sleeps with her downstairs neighbor occasionally but refuses to date anyone, whispers “I repent nothing” into the mirrors of a hundred hotel rooms from London to Singapore and in the morning puts on clothes that make her invincible, a life where the moments of emptiness and disappointment are minimal, where by her mid thirties she feels competent and at last more or less at ease with the world, studying foreign languages in first-class lounges and traveling in comfortable seats across oceans, meeting with clients and living her job, breathing her job, until she isn’t sure where she stops and her job begins, almost always loves her life but is often lonely, draws the stories of Station Eleven in hotel rooms at night” (Mandel, 107).

Miranda is divorced at twenty-seven, a time where everyone around her is probably entering their first marriage or accelerating rapidly into their adult lives. Divorce at such a young age poses a new beginning. Where will she go next? It seems like a rest, a sudden freedom after experiencing such hardship. The way it’s phrased, paired with her place in Toronto, a feeling of moving to a new city. Pain. Freedom.

The description is all in one sentence; occupying an entire paragraph that dominates the page. It seems never ending, the way in which the clauses build on each other. There exists some momentum to the page, a relentless force surging forward past every plausible end point. I find hope in this narration, this refusal to stop where expected. In many ways, it’s true to life. We live in a stream of consciousness that never has neat ends, never is perfectly wrapped up in the way a period perfectly brings a sentence to a close.

Of course, this force moving Miranda into the future is herself, her dedication to her craft. I’ve felt this way more than enough times this semester, in fact, this entire year. Needless to say, I’ve been buried in work. I’m not alone in this pursuit, as I recognize this same workload in many of my classmates, yet isolation has followed this tremendous undertaking of senior year.

TANGENT

I can’t study at home. I’m not sure what about the familiar walls of my house prevents me from being productive, yet there’s a peace I feel when at home, free from pressure. I’d hope to keep it this way. I find myself much more productive in a coffee shop, or in a spare room in the Upper School. There’s motivation in being in public, in not being able to take breaks without being conscious of what you are doing and why. Working elsewhere forces you to use your time in productive ways, there’s an accountability in not being in the privacy and comfort of your own home. I’ve been using my time at home as an escape. When I’m there, I do nothing but relax and eat. It’s my motivation. Everyday I wake up, go about my day, so I can go home. Is that sad? Not sure. Many nights this means I don’t get home until 10pm, or whenever I get kicked out of whatever coffee place I’ve hunkered down in for hours on end. Over this past semester, out almost every night trying to get all my assignments done, staying in on the weekends, it’s been incredibly lonely. I feel distant from my family, who only sees me rushing out of the house in the morning or coming home in tears from a weekly breakdown.

TANGENT in a TANGENT

True story: I had an emotional breakdown on a Thursday a couple weeks ago. I remember vividly the feeling of fear and stress overwhelming me as I sat, as I do now, at a large wooden table in my local Caribou (where I once worked). I drove home in tears, slightly blurring my vision (very unsafe), and arrived home to vent to my worried parents, who often assume I’m okay because that’s the persona I present. Anyways, I’m always at my house on the weekends. Since I’m only ever there to sleep during the week, I like to use my weekends to sleep, perchance to dream, or to lay mindlessly on the couch. While it’s incredible to recharge, I realize everyone else my age is out partying or staying up late. It’s strange, how I feel I’ve grown 20 years in a matter of months, the sudden urge to go to sleep at 8pm, the comforting feeling of a hot tea after a long day. Where is my youth going? I’ve been living my studies, “breathing” my studies (107). I guess, just like Miranda, I don’t know where I stop and my work begins.

I admire the passage’s use of imagery and description, interloping them to a certain rhythm. It’s as if massive amounts of time pass quickly yet stop on specific sights, benchmarks along the way, creating an effect of nostalgia hidden amongst movement, like a visible sad undertone. To the “comfortable seats,” to drawing Station Eleven “in hotel rooms at night” (107). This cadence, a tangible energy of fearless, yet passive living. I’m living like this. Running from something, some unresolved part of myself that refuses to be acknowledged, but is ignored through plunging into work. For Miranda, that’s other people. It might be the same for me.

Independent comes to mind when I think of this character, a word I’ve frequently used to describe myself (you could probably find it in my first letter). Miranda has been hurt by Carlos and Arthur, leading her to swear off dating, swear off other people. It’s a trope we see in Her, and in anyone who has ever been hurt or made to feel as if they are completely alone or unwanted. I love my life, and for good reasons. I go to an amazing school, soon to be college. I have loving parents and friends, yet, like Miranda, I’m often lonely. For a long time I refused to be open with myself or with others, and still I refuse to date anyone, to feel anything other than stress and laughter. Is this oversharing? I guess it’s literary therapy.

In a similar way, I use clothes to project an image of someone who has it together, someone who is in tune with himself and everyone else. I derive confidence from a good outfit or a compliment I might get in the halls. My reliance on this confidence has only gotten worse this year, in times where I feel entirely in limbo. Through the college process, it seems my entire life has been on the line, with strangers in private rooms thousands of miles away reviewing every facet of my life, deciding if I’m deserving of something I know I’m deserving of. It’s a lack of validation, of stability. To substitute, I use clothing. I use it as armor. I consider myself a fairly emotionally intelligent person. I’m incredibly self aware. I feel I’ve developed a primary relationship with myself, choosing to rely on my own efforts rather than the comfort of others. Perhaps this is why I connect to Miranda’s fierce independence, her refusal to be hurt again by others.

Yet, there’s this moment, a vulnerability to Miranda’s character: Station Eleven. It’s her outlet, her happiness. Reading Miranda’s story, I began to wonder what my Station Eleven was, what kept me going despite the loneliness, what transported me out of my life and into a dream world. It certainly can’t be chocolate chip pancakes or Scandal binges, as those merely exist to pass time, not to challenge it. As I’ve realized, I turn to my nightly reading in moments of distress. Above everything, this course has been my Station Eleven. Throughout the semester, it’s been what I return to when everything seems to be spiraling. I guess that’s a testament to the way the material makes me feel — human, instead of mechanic.

October — The Road

We continued to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, a strikingly uncertain portrayal of life after civilization. As I stated in my essay, “The opening passage reads,’Like pilgrims in a fable’ (McCarthy, 3). A fable, a fictional tale with a moral, instructs the reader that they have something to learn from these travelers. Their story is meant for us.” Reading McCarthy’s masterpiece, I learned the nature of complacency, and of the threat it poses to our life and health, both as individuals and as a population. Fearing this work-revolved lifestyle I was slipping into, The Road gave me the needed jolt that brought me to awareness. “Borrowed time and borrowed world and borrowed eyes with which to sorrow it,” McCarthy wrote in reference to the Man and the Boy (130). Repetition hammers this phrase into the mind of the reader, asserting a fragility to our world. Just as the Man and the Boy, we are living on borrowed time, especially since our world is slowly descending into climate-fueled chaos. The pulchritude of this phrase sunk into my mind as would butter on toast (or Offred’s face), confronting me with my own mortality. I felt vulnerable and panicked at the same time. I shouldn’t be spending my time trying to slough my way to the next day, to the next sleep, the next assignment. If I’m living on borrowed time, what’s the point in wasting it?

I started The Road on the couch in the back of Spyhouse, trying to shake off anxiety from studying for a Bio exam. In the opening pages, I read, “An old chronicle. To seek out the upright. No fall but preceded by a declination,” the words floated up in the air (15). Unease radiates off of this powerful sentence in the opening pages of the novel, having a universal, timeless application as the “old chronicle” collides with the narration from the near future. I became conscious of my own actions, asking myself if I was contributing to a decline. I asked myself if I was being selfish, repeating old mistakes through refusal to live consciously. Towards the end of the novel, McCarthy writes “That the space which these things occupied was itself an expectation,” referring to a collection of books in a library demanding to be read and put to use (187). Literature is meant to inform our decisions moving forward, to disrupt our way of thinking and lead us to better lives. McCarthy’s words, in my opinion, intended to warn us of our own potential. We have the answers we seek, and are responsible to see them through. The only thing that stands in the way is ourselves. As I learned through The Road, complacency is selfish and ultimately, dangerous to others. We cannot be apathetic. We simply can’t afford to.

I was silent upon finishing this novel; finding no use in speaking. You already know how deeply it impacted me to realize where my panic, my urgency, came from. Funnily enough, writing my essay, I was lost in admiration for the way in which McCarthy writes. It’s simply incredible. The simple changes in form and diction turned a novel into a transcendent piece on human existence, not merely the story of two nameless skinny guys starving for 300+ pages, as some Road haters often said. Don’t even get me started on the existence of those shriveled apples. I digress again, ugh.

November — Her

Oh god. What do I even say about Her. I could, and I will, praise the acting. Kristen Wiig was simply transformational as “SexyKitten.” Also, Scarlett Johansson brought such a strange humanity to a voice-only role, it’s kinda creepy (take notes Siri).

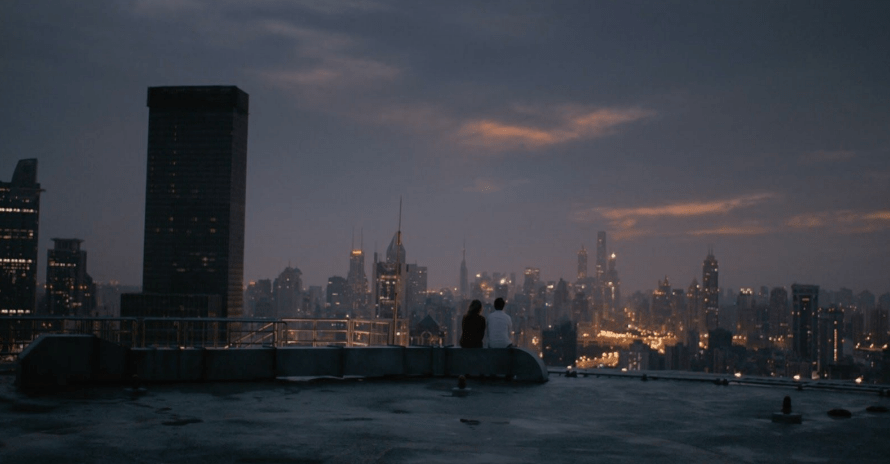

Ultimately, every time I think of this film I think of the final shot.

The shot itself is like a breath of fresh air after the deep sadness of loss as Samantha and the rest of the OS systems leave forever. Our characters, those we know and love, sit at the precipice of the rest of their lives, small individuals in the face of a large, expansive city. The buildings stretch as far as can be seen, extending beyond our horizon, beyond our conception of a limit. The shot is simply so hopeful, like the opportunity in moving to a new city. The world feels opened in a single second. A moment of intimacy defines this image, drawing the reader to Amy and Theodore, who in the face of a brave new world without their OSs, turn to each other for comfort. It legitimizes their relationship and leaves the viewer with hope, as any romance movie should. It’s also a return to the physical, to the world of humans. The entire film has centered on these OS systems that occupy “the space between the words.” However, this scene causes us to reflect on the accomplishments and power of humans. It restores our faith in humanity, offsetting our previous dependence on the OS. I truly can’t stop thinking about this one image. I don’t have any crazy takeaways, in fact I’m still trying to figure out what it taught me. I know it coasted in the back of my mind for a few cold weeks, like riding a post-exam high. It made me appreciative, in a way.

TANGENT

Through discussion, I learned that many of my peers thought this scene would end in Amy and Theodore jumping to their deaths. While I never imagined this ending, I found its possibility made all the difference in this final scene. In a second, one single movement, they could’ve jumped, could’ve ended their lives and their stories, yet they chose to live, to see the city in its entirety. I choose to see this as beautiful.

November/December — The Handmaid’s Tale

In my reading of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a show I’m still waiting to see on Hulu (if anyone gives up and lets me use their account), I realized the utter power of language. Separate from the “newspeak” of George Orwell’s 1984, language in The Handmaid’s Tale is manipulated by those in power and cherished by those forbidden to read or write.

After reading the historical notes that epilogue the novel, I was hit with the acute realization that in language lies power. The manipulation of phrasing and euphemisms allows the author to attach whatever connotation they feel to a concept without the gravity of the phrase. In The Handmaid’s Tale, places where women were held against their will and indoctrinated, forced to watch videos of gruesome mutilations, and ultimately tortured, was called a “Re-Education Center,” as if it was a office space for physical therapists (305). Similarly “the ceremony” and the “salvaging” are extreme euphemisms for the activity in each, one being rape and the other being a “general term for the elimination of one’s political enemies” through mass trauma, respectively. (Atwood, 93, 307). Ultimately, at the “Twelfth Symposium on Gileadean Studies” the “Underground Femaleroad” of the early Gildean period is referred to as the “Underground Frailroad” (which made me mad) (301). The substitution of “frail” for “female” patronizes the refugees of this oppressive regime, making them seem weak for choosing to leave rather than validating their fears and trauma experienced as a Handmaid, Aunt, Martha, or Wife (or perhaps as any Woman, anywhere).

“Larynx, I spell. Valance. Quince. Zygote. I hold the glossy counters with their smooth edges, finger the letters. The feeling is voluptuous,” Atwood writes as Offred plays Scrabble with the Commander (139). Offred’s description of the feeling of the letters is almost sexual. “Voluptuous” and “finger” are used in reference to a simple action of touch, the speaker seemingly simulating sex with the letters, using a passion unseen throughout the novel in her character. To those without access to literature, without writing, its euphoric to hold the power of language. Similarly, Offred’s catchphrase “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum,” gives her strength when needed (52). Before the ceremony, Offred recites the phrase in her memory, reflecting: “I don’t know what it means, but it sounds right” (90). The mere placement of the phrase is a rebellion, and in such a way there is strength in its opposition to the status quo. Finally, as the novel nears its close, I began to notice Offred’s fading spirit, her hope slowly diminishing. Using an apostrophe, Atwood turns Offred’s narration to the reader, she narrates: “By telling you anything at all I’m at least believing in you, I believe you’re there, I believe you into being.” (268). We tell stories so that they are heard. As McCarthy wrote in The Road, “That the space which these things occupied was itself an expectation,” (McCarthy 187). Literature gives us power, it places hope in future generations in ways we can only feel, not see. In my attempt to apprehend all of this, I left with a resounding feeling of responsibility to listen and to adapt based on the lessons I learn through my readings. I’ve done my best to do this since.

December — The Birds

The opening scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds shows Melanie Daniels freely walking around San Francisco, ultimately deciding to go into a pet store where hundreds of birds sit behind cages. Melanie, immediately, stands out as a character. Her outfits are bold, well coordinated, and accentuate her strong personality and, often, her witty comments (sound familiar?). Melanie is assertive and nontraditional, an archetype in conflict with expectations of previous generations. Melanie is seen using birds to her advantage to impress Mitch Brenner, posing as the owner of the pet store (hilariously) and using the lovebirds as an excuse to see Mitch in Bodega Bay. In the town, she sticks out like a sore thumb. Compared to her scenery, Melanie is brightly colored, bubbly, and refuses to be quelled into submission by Mitch or Lydia.

At times I feel this way, like certain groups of people might not be ready for me yet, as if there is some waiting game to where I can be without judgement. Contrary to the characters of Bodega Bay, I admire Melanie. Her confidence aside, she radiates kindness while forfeiting none of her personality or strength of character. I hope I don’t forfeit myself.

However, as they must always do, the birds attack. Coincidentally, they begin just as Melanie arrives in Bodega Bay. The first attack we witness is directly on Melanie, where she is cut approaching Mitch on the dock. Throughout the rest of the film, the birds follow Melanie, attacking at key moments in her relationship with Mitch. When Melanie decides to stay for Kathy’s party, a bird crashes into Annie Hayworth’s door. At the party, as Melanie and Mitch bond over shared stories of childhood, the birds attack again, and again when Melanie decides to stay the night with Mitch. These birds almost coordinate attacks when Melanie grows closer to him, seemingly emulating the spirit of Lydia, who at first doesn’t approve of Melanie’s character for her son. As mentioned, Melanie had had an incident in Rome, where she jumped naked into a fountain (when in Rome?), much to the disdain of Lydia later on. It’s clear throughout the movie, as well as the mention of Melanie’s stint in court in the opening scene, that Melanie refuses to follow rules, refuses to be domesticated. In every instance of connection with Mitch, she is calling the shots and staying independent. However, the final scenes of the play see Melanie viciously attacked by the birds through a hole in the attic (convenient, huh), resulting in her leaving bloody and battered in Lydia’s arms. When Melanie is completely vulnerable and trusts herself to Lydia, shown by the moment of connection the two share in the car as they attempt to leave, the birds allows them to. It’s as if the birds simply wanted to domesticate her, deconstruct the part of her that was wild and fearless. The film even goes as far as to construct the image of Melanie at the end of a hall of traumatized victims of the bird attacks, one woman turning to Melanie in tears and yelling: “I think you’re the evil.”

This is sadly unavoidable. Throughout life, we will always be belittled, be made into something we’re not. I struggled with this, as I imagine everyone did, during the college process. I felt as if I was so much more than a double digit number on a scale of 1–36, as testified by the ACT that constantly appeared in reminders of national averages and college ranges. Similarly, I feel this pressure in school. Test scores and GPAs aside, I always was aware of what was socially acceptable and what wasn’t. I felt as if I was trying to fit myself in a box, and that angered me. During my junior year, I decided to stop caring about whatever boxes I was being forced into, whatever limitations were placed on me by those who don’t know and don’t care about my happiness or free will. I started dressing as I pleased, being honest with what I wanted, and staying true to the part of myself that transcended scores and quantitative measurements of success. While this period of growth may not have been triggered by viewing The Birds, or the resulting trauma of hearing Izzy and Sara scream as they were attacked, Melanie’s struggle certainly reminded me of the importance of remaining who you are despite opposition.

Now

As I’m writing this paper, I was just made aware of 0.5 point difference in my AP U.S. Government and Politics exam average, one that determines my grade for the semester, and what feels like my whole life. It gave me a headache. Oddly enough, I’ve been drinking water all day (move on, William). Anyways, I found myself so torn up about this small point, about what minute detail caused such crazy ramifications, and then I came back to this letter, and my headache disappeared.

I find the ability to be free in my pursuit of knowledge is what has made me fall as deeply in love with this course as I have. The world doesn’t rest on a half a point when I’m in this class, when I’m disappearing into my Station Eleven in the back of coffee shops or on the bus back from a Nordic race. I want to thank you for creating an atmosphere where this was possible, it’s made all the difference in my happiness and learning.

I realized I’ve gone over the page limit, and I’m currently writing in 11 pt font, 1.15 spacing. I apologize for the extra reading, I’m fairly long-winded when it comes to essays. As I’ve realized, the best work I’ve done is never constrained by details and is never made to satisfy requirements (although my use of a semi-colon may have been). Beyond everything, beyond all the noise, I’ve been continually surprised by the power of literature to inform our decisions, both past and present. I thank you for the reading list and the opportunity to learn authentically. I’m glad I fought to stay in your block 1 class next semester.

I finished my coffee. Oops!

Leave a reply to dolphinwrite Cancel reply